The Cassowary: Why We Should Care

October 11, 2023 | Uncategorized

from Anne Montgomery

It’s estimated that nearly 500 animal species have become extinct since the beginning of the 20th century. Among them the Passenger Pigeon, Japanese Sea Lion, Western Black Rhinoceros, Golden Toad, Caribbean Monk Seal, and Mexican Grizzly Bear, now gone forever.

And yet, for most of us, the absence of these creatures makes no difference in our daily lives. Perhaps that’s why some people roll their eyes when they hear about saving the tiny Snail Darter or the Polar Bear or the Gray Wolf.

But what if a creature existed that could change lives with its passing? And I mean change in a big way.

Meet the cassowary.

I first became aware of the giant, Australian bird that vaguely resembles an ostrich, but which sports a fabulously-colored keratin casque, while walking in the Daintree Rainforest – a UNESCO site like the Great Barrier Reef over which it hovers – that has one of the most complex ecosystems on Earth, hosting species whose ancestors date back 110 million years.

I first became aware of the giant, Australian bird that vaguely resembles an ostrich, but which sports a fabulously-colored keratin casque, while walking in the Daintree Rainforest – a UNESCO site like the Great Barrier Reef over which it hovers – that has one of the most complex ecosystems on Earth, hosting species whose ancestors date back 110 million years.

“The cassowary is extremely important,” our guide explained. “Without the bird, the forest would not exist.”

Daintree is primordial. Giant strangler figs crawl across the forest floor. Dappled sunlight sneaks though a thick green canopy. Massive ferns sprout from leaf-littered soil. The outside world is muted, and the sight of a dinosaur might not seem strange.

I learned the cassowary is a one-bird master gardener, a creature that combs the forest floor eating fallen fruits, even gobbling up plants that are toxic to other creatures. The bird consumes up to 150 different types of fruits. The existence of 70 to 100 plant species depends on the cassowary pooping out their seeds in a pile of protective, compost-like dung, the smell of which repels seed predators. The cassowary is a “keystone” species, which means a species on which others in an ecosystem largely depend, one that, if removed, would cause the ecosystem to change drastically.

So, no cassowary, no rainforest. But there’s more. Below Daintree are mangroves, a mucky area rich in bio-matter that filters down from the forest. All types of young creatures – crabs, jellyfish, snappers, jacks, red drums, sea trout, tarpon, sea bass, and even juvenile sharks – thrive in the protection of the fertile water of the mangroves.

Offshore, the Great Barrier Reef follows Australia’s eastern coast. There, too, the nutrients from the forest help feed the tiny creatures that build the reefs. This fertilizer promotes the growth of phytoplankton which nourishes the zooplankton on which the coral polyps dine. Without this sustenance the coral dies, losing the ability to protect the shoreline from waves, storms, and flooding, which leads to loss of human life and property.

Also consider that roughly 25% of the world’s fish species spend part of their lives on the reefs. If the Great Barrier Reef dies – note that half of the more than 1,400-mile structure has already perished – vast fisheries could collapse leading to starvation that could ultimately affect billions of people.

Which brings me back to the cassowary. It’s estimated that only 12,000 to 15,000 of the birds remain in the wild. Loss of habitat is decreasing their numbers, as are attacks by dogs. Another problem is humans driving too fast.

Why should we care?

I think the cassowary is but one example of the interconnectedness of life. Perhaps that’s something we should think about.

Please allow me to offer you a glimpse at my latest women’s fiction novel for you reading pleasure.

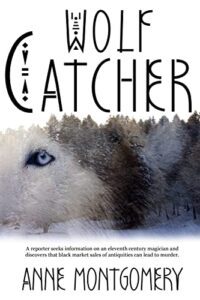

The past and present collide when a tenacious reporter seeks information on an eleventh century magician…and uncovers more than she bargained for.

The past and present collide when a tenacious reporter seeks information on an eleventh century magician…and uncovers more than she bargained for.

In 1939, archaeologists uncovered a tomb at the Northern Arizona site called Ridge Ruin. The man, bedecked in fine turquoise jewelry and intricate beadwork, was surrounded by wooden swords with handles carved into animal hooves and human hands. The Hopi workers stepped back from the grave, knowing what the Moochiwimi sticks meant. This man, buried nine-hundred years earlier, was a magician.

Former television journalist Kate Butler hangs on to her investigative reporting career by writing freelance magazine articles. Her research on The Magician shows he bore some European facial characteristics and physical qualities that made him different from the people who buried him. Her quest to discover The Magician’s origin carries her back to a time when the high desert world was shattered by the birth of a volcano and into the present-day dangers of archaeological looting where black market sales of antiquities can lead to murder.

AMAZON BUY LINK

Anne Montgomery has worked as a television sportscaster, newspaper and magazine writer, teacher, amateur baseball umpire, and high school football referee. She worked at WRBL‐TV in Columbus, Georgia, WROC‐TV in Rochester, New York, KTSP‐TV in Phoenix, Arizona, ESPN in Bristol, Connecticut, where she anchored the Emmy and ACE award‐winning SportsCenter, and ASPN-TV as the studio host for the NBA’s Phoenix Suns. Montgomery has been a freelance and staff writer for six publications, writing sports, features, movie reviews, and archeological pieces.

When she can, Anne indulges in her passions: rock collecting, scuba diving, football refereeing, and playing her guitar.

Learn more about Anne Montgomery on her website and Wikipedia. Stay connected on Facebook, Linkedin, and Twitter.